It is always a treasure hunt going through the Backwoods Shoppe. From the diversity of the donations we receive, there are so many interesting items that sometimes you just don’t know where to look. A few weeks ago, while checking our vintage glass bottles for pricing, I came across this strange looking heavy glass bottle. When I examined it, I realized that there was a glass ball in the neck of the bottle. So of course, I had to research it. And down the rabbit hole I went.

This type of bottle is called a Codd-Neck bottle. It was designed for the use of early carbonated soft drinks, designed in 1872 by Hiram Codd of Suffolk, England. A mechanical engineer by trade, he realized that there was a need for a better design for carbonated mineral water. Prior to this, carbonated drinks were bottled in jugs with corks which allowed gas to leak causing them to go flat. Cobb’s innovations included the use of heavy glass bottles, a glass ball, and a gasket seal. The bottles were filled upside down.

In Cecil Munsey’s 2010 article, “Codd (Marble-In-The-Neck) Soda Water Bottles, Then and Now,” he says: “His bottle used the effervescent pressure of the mineral water itself to force a marble against a rubber washer in the upper ring of the neck of the bottle. This made for a very efficient and durable seal.” It is said that some of those bottles remained sealed for more than 100 years! Codd licensed bottlers annually for the use of his design and was the standard for carbonated drinks for 50 years.

Codd also designed a custom opener for the bottles which was inserted into the neck to allow the gas to escape and open the bottle. These openers were mainly used in public settings. However, regular consumers would use their little finger to push the marble down and open the bottle.

In the late 1800s, with the development of the crown top for sealing carbonated drinks, marked the beginning of the decline in using Codd-Neck bottles. Codd neck bottles have since become a collector’s item in England due to children breaking the bottles to get to the glass balls.

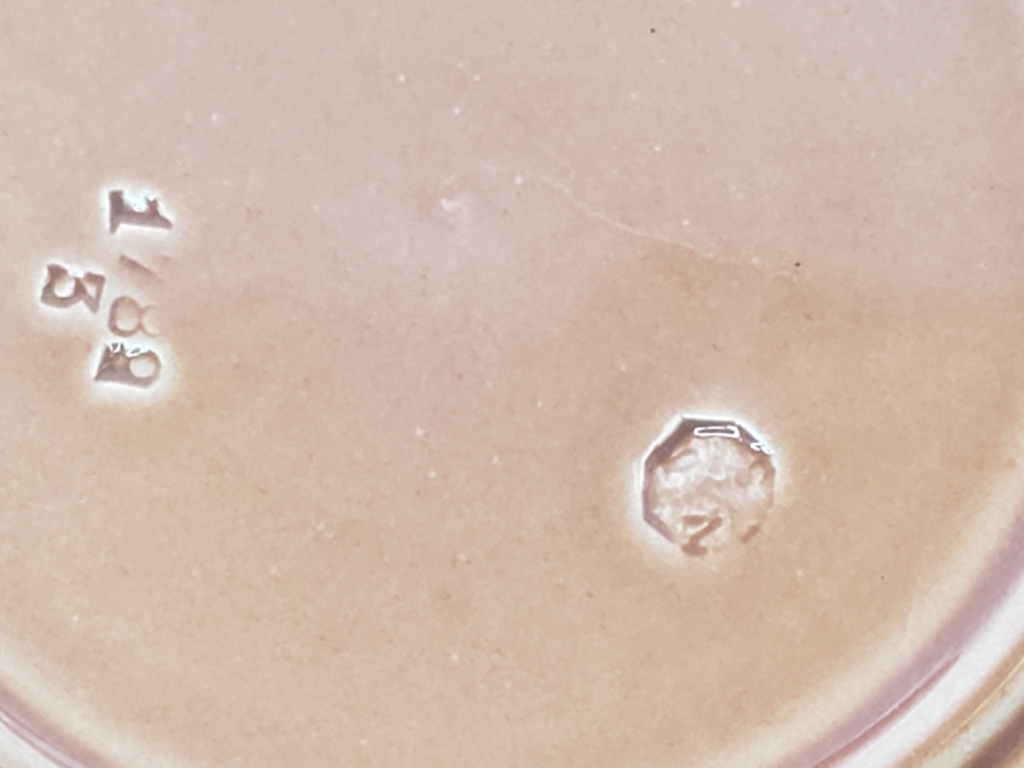

The bottle that we have is an embossed C. Barraclough – Harrogate with a rose. In my search for information on the company, and I searched everywhere on the internet, I couldn’t locate any real information on C. Barraclough – Harrogate. While there are plenty of references to the sale of the bottles, there is little to no information for the company. I did find an advertisement in the first page of “The Handy Guide to Harrogate and District.”

The design is still used in India for a drink called Bantu and in Japan for lemon drink called Ramune.

Please take the opportunity to go to The Backwoods Shoppe Etsy page to see our listing for a Codd-Neck bottle – as well as other fun and unique finds we have available. Feel free to visit our Instagram and Facebook pages and follow us!

https://www.beachcombingmagazine.com/blogs/news/history-the-codd-neck-bottle